Billion-dollar manufacturing, aerospace, and automotive companies rely on CAD to build highly precise 3D models. But it might shock most people to know that the technology powering these massive industries is built on a broken mathematical concept.

Boundary representation (b-rep for short) is the math that describes geometry in CAD. Every CAD system today is built on a geometry kernel that is the software implementation of b-rep math.

While b-rep kernel developers have done an amazing job implementing algorithms that allow CAD software to perform complex operations, CAD users are familiar with the headaches that arise when operations fail. Because you can’t build a robust geometry engine on broken math.

Here, we’ll get into the basics of b-rep, its inherent problems, and how those problems might show up in your CAD models.

What is b-rep, and why do we use it in CAD?

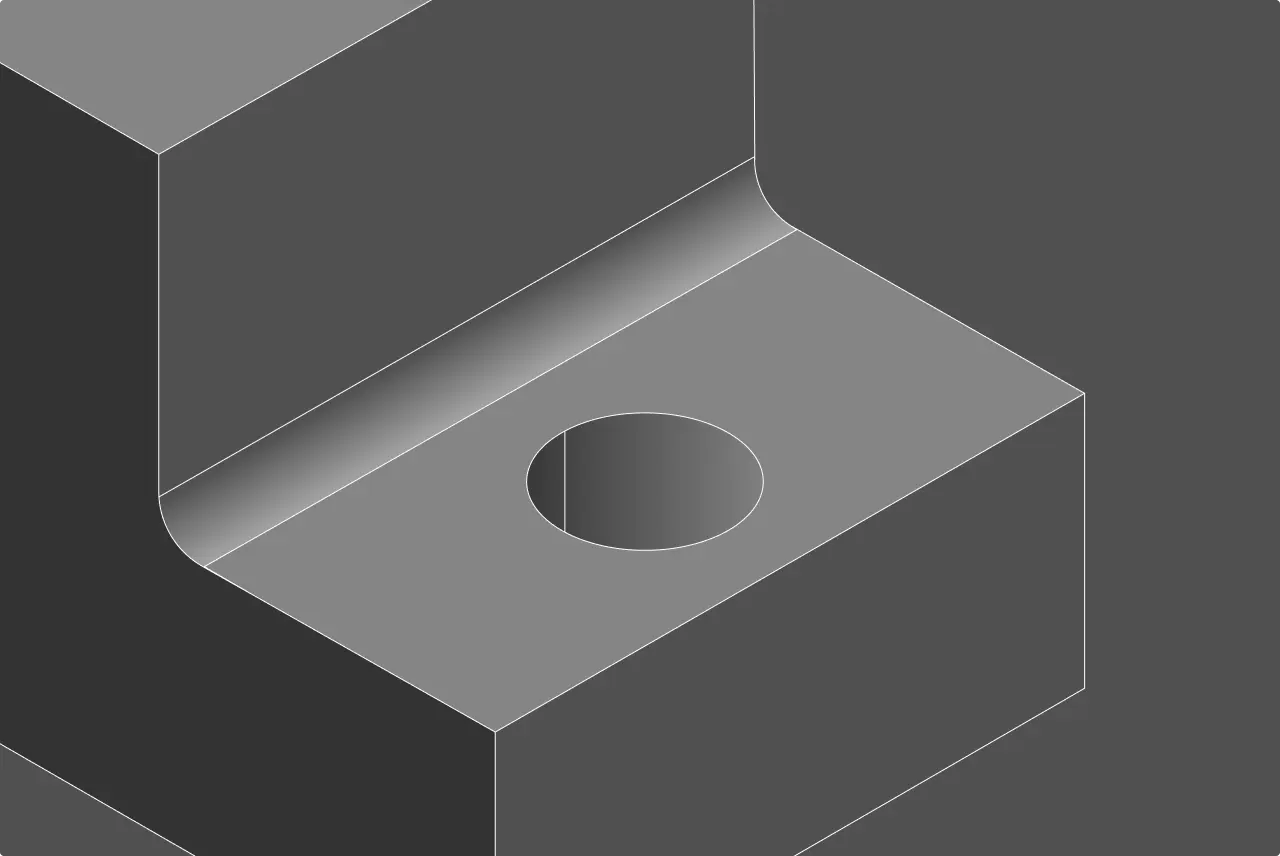

B-rep is the mathematical basis for describing geometry in computer-aided design and computer graphics. It defines how a shape is represented using the shape's boundaries.

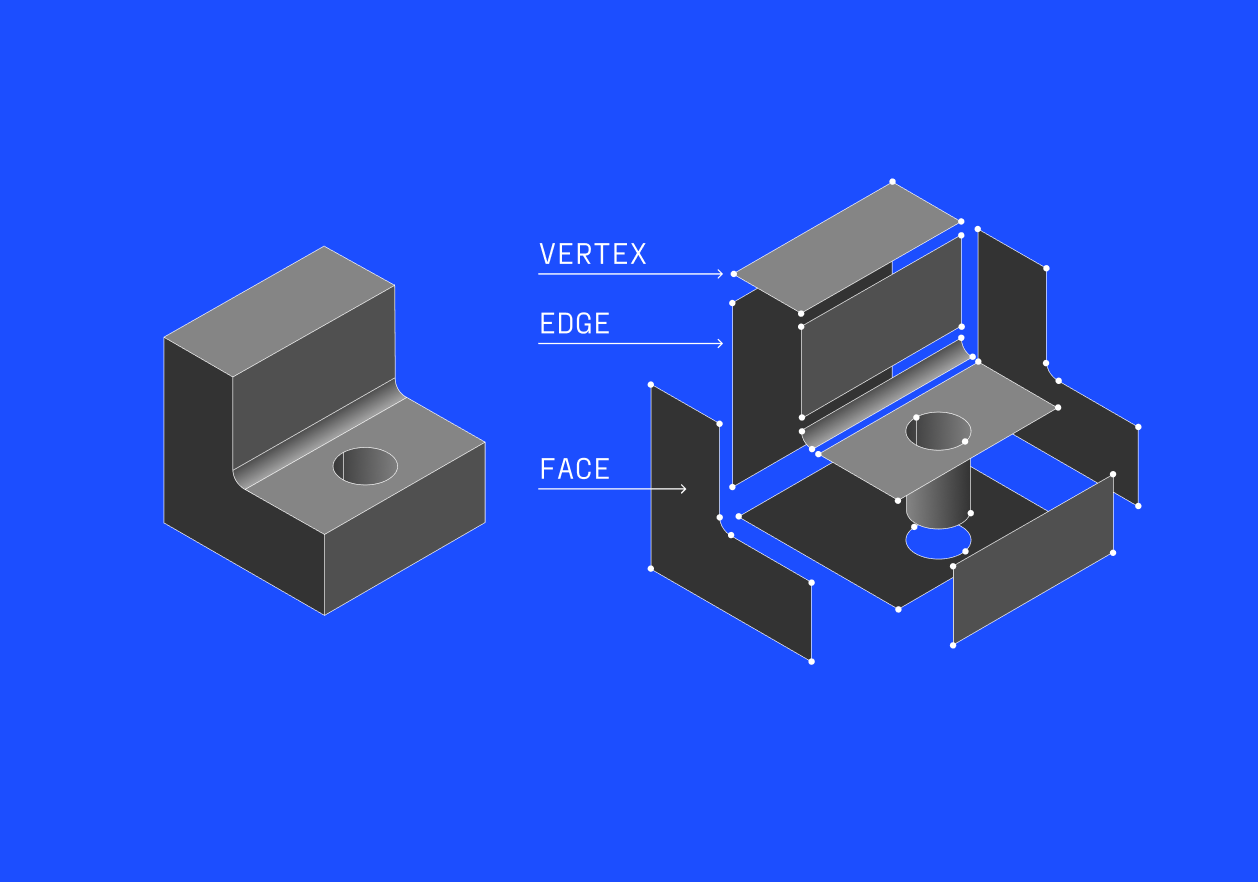

For example, an edge is a parametric curve with one, two, or zero vertices that define its boundaries. A face is a parametric surface, bounded by edges laying on the surface, that define the borders and the holes of the face. A solid body is one or more faces sewed together along their edges that form a closed volume.

B-rep has unique properties that no other geometry representation has:

- The concept of faces and edges is natural and easily understood by humans — we see a cube and we understand that it has six faces, and that two faces meet at an edge.

- B-rep provides geometry and topology, as well as an interaction model to select and manipulate geometry.

- The parametric surfaces and curves of a b-rep model are extremely accurate and can be used for manufacturing high-precision parts. That makes it better than mesh models, which can only approximate curved surfaces using polygons.

- B-rep has become the language, the “protocol,” between CAD, CAM and CAE applications. If an application can read and write b-rep files, like a STEP file, then it’s going to be reasonably compatible with most other CAD, CAM and CAE applications.

Sounds great, right? Not so fast. There’s a problem — actually, several problems — that make B-rep models fragile.

The problem with b-rep

Boundary representation has some intrinsic disadvantages that are impossible to overcome, regardless of the great efforts that kernel developers put into building state-of-the-art b-rep kernels since the 1980s.

These disadvantages translate to broken geometry, failing geometry operations, performance and scalability problems, and other CAD issues that can then lead to manufacturing errors.

1. There’s no universal definition of how operations should work

B-reps define 3D shapes, but it doesn’t provide a universal concept for changing and editing the geometry.

While there are lots of different operations you can use to change a shape in every CAD, like boolean operations, extrusion, chamfers and fillets, and more, there isn’t a uniform, standard algorithm that would provide a generic solution for these operations for every different b-rep geometry.

As a matter of fact, every operation would need to cover an infinite number of edge cases for every potential geometry and topology combination to provide a robust solution. This is obviously not possible, so kernel developers keep implementing edge cases to increase the robustness of their implementations over decades.

Despite this heroic effort, CAD users will keep running into failing booleans, fillets, shells, because it’s impossible to cover all the edge cases, and if the kernel developer did not implement that particular use case that the user asks from the kernel, the operation will fail.

2. Tolerance isn’t universally defined, either

Since b-rep works with floating-point numbers and numerical algorithms, “equal” doesn’t always mean “exactly the same.”

Two points are considered equal, not if they are at the very same point, but if they are a very, very small distance from each other. Tolerance is the number (typically 10^-6 meter or less) that defines whether two points, curves, and surfaces are considered the same.

The problem?

- Tolerance is defined by the kernel. Two different kernels might have two different numbers for managing tolerance.

- Working with tolerant geometry further explodes the number of potential edge cases.

You can see how that becomes an issue in the following scenario:

- CAD1 is running on Kernel1, which uses 10^-5 meters as a tolerance for equality. CAD2 is running on Kernel2, which uses 10^-6 meters as its tolerance.

- CAD1 creates a cube where the end points of the three lines in a corner are 0.5 * 10^-5 meters away from each other. Kernel1 defines this as the same point.

- You export the cube to CAD2, which has a different tolerance. The solid cube ends up being a set of disconnected faces according to the geometry. However, the topology still says that it’s a solid body.

- This forces Kernel2 to do all sorts of magic (called geometry healing) to make topology and geometry consistent. It can either blow up the cube and turn it into 6 separate faces, or try to manipulate the geometry to turn it into a solid object in the world of Kernel2. Either way, we will end up with different geometry, which can cause all sorts of manufacturing errors.

Since b-rep works with tolerances, geometry and topology data are somewhat independent. But while the two data structures are independent, what they represent is not.

Thus, the kernel continuously needs to do double bookkeeping of two complex data sets and be able to handle an endless amount of corner cases and inconsistencies that are the inevitable by-product of b-rep operations.

Examples of b-rep fragility

But it’s just math, right? Well, this is the problem: it’s not just math. There is no universal formula for how to implement topology changes from a modeling operation.

During a modeling operation (such as a boolean operation, or when a fillet is overflowing, or when the thickness of a shell operation is changed), not only does the geometry (shape) of the faces and the edges change, the connectivity graph of the faces and edges change, too. For every single topology change, there is a different implementation in a geometry kernel.

Robust b-rep kernels like Parasolid have, over decades, implemented hundreds or thousands of different variants of topology changes for every operation. But it can’t be perfect.

Sometimes, a user will try to complete an operation for which there is no implementation, and the operation will fail, like in this case:

When the blend starts to overflow around the cutout, it suddenly expands to the neighboring edge, which is expected. However, at a certain point, the fillet radius cannot be increased further.

Other times, when the b-rep kernel runs into a problem implementing a topology change, it’ll result in some unexpected behavior, like this:

In this case, things work as expected until the fillet reaches the bottom edge. When the blend overflows, Parasolid decides to “eat” the cutout and the added material. This isn’t intentional, but it’s likely that there is a similar case where this behavior makes sense — and the kernel decides to use that implementation for this case, too.

Is there a solution to the b-rep problem?

If none of the kernels currently powering CAD systems are perfect, why not just build a newer, better b-rep engine? There are a couple of reasons why that isn’t the answer:

- B-rep is the problem, not the kernel. The math that boundary representation is based on is broken, so you will run into the same issues.

- The best b-rep kernels, including Parasolid, have implementations for zillions of different geometry combinations for different edge cases that have been built up over decades using customer data. A new b-rep kernel won’t be able to cover every edge case without customer data, but nobody will use a kernel that doesn’t have a robust number of edge cases covered.

B-rep may have its shortcomings, but it’s also become the standard for the CAD ecosystem. Does that mean we’re stuck with b-rep? Maybe not, but it does mean that any new solution would have to be compatible with b-rep while solving for the issues we discussed above, like the double-booking of geometry and topology data.

Check out my other CAD deep dives for more technical breakdowns, and let me know what topics you want to hear about next.